Fruit is one of those types of foods that seems to be in constant controversy. You’ll hear some say that fruits have always been good for us and we should eat them often, and you’ll hear others say that they are just sugar-bombs and should be avoided just like soft drinks.

Today we’re going to go through the two big myths surrounding fruit and dig into the science to see what the evidence really says about fruit.

Myth 1: The sugar in fruit leads to weight / fat gain

This myth has been populated by Lustig and co. and the “insulin hypothesis of obesity”. I’m not going to get into the details of the “insulin hypothesis” (that will be for a future blog post), but I will go into some of the broader aspects.

Essentially, this hypothesis states that sugar leads to a rise in insulin, and one of insulin’s main jobs is to store things like sugar into cells, including storing it into fat cells. Moreover, insulin blocks the ability of fat to be released from the fat cell (i.e. lipolysis). According to the hypothesis, this double whammy leads to fat gain from sugar and carbs.

Nice hypothesis, and it seems logical at first glance. Yet this is one of my pet peeves about the nutrition field as a whole: people are talking about hypotheses when they need to be talking about evidence.

Again, I won’t go into all the research surrounding the insulin hypothesis in this post (it would need the space of a small book), but suffice it to say that this nice-sounding theory ends up falling flat on its face. I’ll write more about this in future posts.

For now, let’s talk specifically about fruit.

- Some fruits, mango in this case, have shown to have pretty pronounced anti-obesity effects in rodent studies. (1, 3, 4)

- Multiple types of fruit have been tested in human studies and almost uniformly are shown to have anti-obesity effects. (2, 3, 5, 6, 7)At the very least, they end up having no effect on fat mass.

“The feeding of apples [to] rats (7-10 mg/kg/d) in different forms in 8 experiments have shown that this caused weight loss during 3 to 28 weeks. In agreement with this, the obtained results from 5 experiments on humans have revealed that consumption of the whole apple or apple juice (240-720 mg/d) in 4-12 weeks by fat people can cause weight loss. Experiments on animals and humans have shown that the consumption of apples in different forms can cause weight loss in overweight ones.” (3)

Thus, the data is very clear on this point:

Regardless of what “hypothesis” or “theories” you wish to believe in, the totality of the evidence shows that not only do fruits not cause weight gain, but they tend to have anti-obesity effects.

Now, I’m not telling you to chug down fruit juice all day long either (and whole fruits are much better than juice), but fruits and their juice in moderation is fine and good for you.

And oh, by the way, whole fruit (not fruit juice) is not a high glycemic index (GI) food group. Fruits are actually low to medium on the glycemic index scale and thus safe for diabetics. In fact, many whole fruits have been shown to have an inverse association with Type 2 Diabetes. (17, 18)

Myth 2: The Sugar in Fruit Creates Inflammation

This myth is even worse than the last one. Nothing could be further from the truth.

While it is true that isolated refined sugar can increase inflammatory markers in humans (especially if put in liquids / beverages) (8), this is not the case for natural sugar found in fruits.

This is because the sugar in fruits has a lot of other things that come with it, including phytonutrients, fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

Phytonutrients include polyphenols, anthocyanins, catechins, carotenoids, etc.

Phytonutrients are really the key players that help explain why fruit is good for you. If I had to choose the number one reason why fruit is far healthier than sugar, it would be the phytonutrients.

Phytonutrients directly lower all types of inflammation and largely protect us from various chonic diseases. (9, 10, 11)

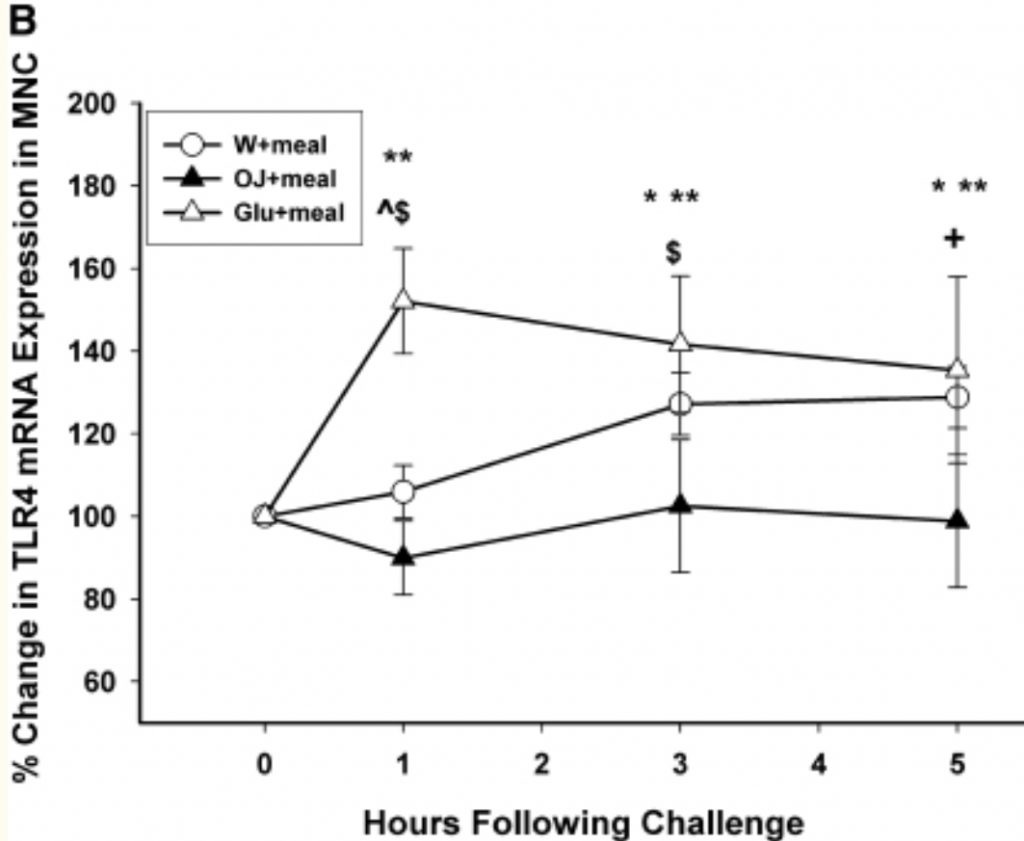

There have been three similar eye-opening studies that were performed in 2011, 2015, and 2017 all testing the same question: What happens when you add orange juice to a “junk food” type meal compared to when you add water or, in the 2010 study, a calorie-equivalent sugar drink? (12, 13, 14)

The results were pretty unanimous: adding orange juice to the “junk food” type meal had significantly broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects. Many markers of inflammation rose when consuming the “junk food” meal with water or a glucose drink, but these markers stayed much closer to baseline when orange juice was added.

In one study, orange juice blocked the rise in the inflammatory marker IL-17A after the “junk food” meal. (14) This is particularly important because IL-17A is correlated with many types of autoimmune diseases such as Rheumatoid Arthritis and Multiple Sclerosis. (15)

Now, I’m not saying that drinking orange juice with all your meals is going to significantly reduce autoimmune symptoms. What I am saying is that making sure every meal consists of whole foods, including fruits that are loaded with phytonutrients, can significantly lower chronic inflammation and thus contribute to protection from autoimmune symptoms and keep you healthy in general. The researchers chose orange juice in the studies above because of how common orange juice is. Yet, any whole fruit rich in phytonutrients will have similar effects. (16)

We’ll talk more about phytonutrients in future articles.

Well there you have it. Hopefully now I have successfully dissuaded you of any fruit-phobia that you may have had! Fruit is incredibly good for you, and humans have been eating it for a tremendously long time. Now, you don’t have to go crazy and eat ALL THE FRUIT or become a “fruitarian” (that’s not healthy either), but go ahead and include some generous servings of whole fruit in your diet!

Please leave any questions or comments below! And please share this article if you feel that you got value from it!

References

- Lucas, E. A., Li, W., Peterson, S. K., Brown, A., Kuvibidila, S., Perkins-Veazie, P., … Smith, B. J. (2011). Mango modulates body fat and plasma glucose and lipids in mice fed a high-fat diet. British Journal of Nutrition, 106(10), 1495–1505. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114511002066

- Evans SF, Meister M, Mahmood M, et al. Mango supplementation improves blood glucose in obese individuals. Nutr Metab Insights. 2014;7:77–84. Published 2014 Aug 28. doi:10.4137/NMI.S17028

- Asgary, S., Rastqar, A., & Keshvari, M. (2018). Weight Loss Associated With Consumption of Apples: A Review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 37(7), 627–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2018.1447411

- El-Shazly SA, Ahmed MM, Al-Harbi MS, Alkafafy ME, El-Sawy HB, Amer SAM. Physiological and molecular study on the anti-obesity effects of pineapple (Ananas comosus) juice in male Wistar rat. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2018;27(5):1429–1438. Published 2018 Apr 11. doi:10.1007/s10068-018-0378-1

- Solverson PM, Rumpler WV, Leger JL, et al. Blackberry Feeding Increases Fat Oxidation and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Overweight and Obese Males. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1048. Published 2018 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/nu10081048

- Tsuda T. Recent Progress in Anti-Obesity and Anti-Diabetes Effect of Berries. Antioxidants (Basel). 2016;5(2):13. Published 2016 Apr 6. doi:10.3390/antiox5020013

- Sharma SP, Chung HJ, Kim HJ, Hong ST. Paradoxical Effects of Fruit on Obesity. Nutrients. 2016;8(10):633. Published 2016 Oct 14. doi:10.3390/nu8100633

- O’Connor L, Imamura F, Brage S, Griffin SJ, Wareham NJ, Forouhi NG. Intakes and sources of dietary sugars and their association with metabolic and inflammatory markers. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(4):1313–1322. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.030

- Hussain T, Tan B, Yin Y, Blachier F, Tossou MC, Rahu N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us?. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:7432797. doi:10.1155/2016/7432797

- Lee YM, Yoon Y, Yoon H, Park HM, Song S, Yeum KJ. Dietary Anthocyanins against Obesity and Inflammation. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):1089. Published 2017 Oct 1. doi:10.3390/nu9101089

- Kaulmann A, Bohn T. Carotenoids, inflammation, and oxidative stress–implications of cellular signaling pathways and relation to chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res. 2014 Nov;34(11):907-29. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.07.010. Epub 2014 Jul 18. Review. PubMed PMID: 25134454.

- Ghanim H, Sia CL, Upadhyay M, et al. Orange juice neutralizes the proinflammatory effect of a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal and prevents endotoxin increase and Toll-like receptor expression [published correction appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Mar;93(3):674. Upadhyay, Mannish [corrected to Upadhyay, Manish]]. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):940–949. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28584

- Cerletti C, Gianfagna F, Tamburrelli C, De Curtis A, D’Imperio M, Coletta W, Giordano L, Lorenzet R, Rapisarda P, Reforgiato Recupero G, Rotilio D, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G, Donati MB. Orange juice intake during a fatty meal consumption reduces the postprandial low-grade inflammatory response in healthy subjects. Thromb Res. 2015 Feb;135(2):255-9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.038. Epub 2014 Dec 13. PubMed PMID: 25550188.

- Rocha DMUP, Lopes LL, da Silva A, Oliveira LL, Bressan J, Hermsdorff HHM. Orange juice modulates proinflammatory cytokines after high-fat saturated meal consumption. Food Funct. 2017 Dec 13;8(12):4396-4403. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01139c. PubMed PMID: 29068453.

- Kuwabara T, Ishikawa F, Kondo M, Kakiuchi T. The Role of IL-17 and Related Cytokines in Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:3908061. doi:10.1155/2017/3908061

- Peluso I, Raguzzini A, Villano DV, Cesqui E, Toti E, Catasta G, Serafini M. High fat meal increase of IL-17 is prevented by ingestion of fruit juice drink in healthy overweight subjects. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(1):85-90. PubMed PMID: 22211683.

- Glycemic index for 60+ foods. Harvard Health Medical School.

- Muraki I, Imamura F, Manson JE, et al. Fruit consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective longitudinal cohort studies [published correction appears in BMJ. 2013;347:f6935]. BMJ. 2013;347:f5001. Published 2013 Aug 28. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5001